A retrospective exhibition of the legendary ‘King of Underground’, John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins who captured the spirit of the 1960s through his powerful and evocative images, highlighting an era of extraordinary change and creativity.

For the first time, Elliot is exited to showcase vintage and signed prints by Hoppy, made available exclusively at Elliott Gallery.

orn in England in 1937, John Hopkins, better known as ‘Hoppy’, was one of the best-known counterculture figures in London during the 60s, not just as a photographer and journalist, but also as a political activist.

Hoppy graduated from Cambridge University in 1958 with a Master’s in Physics. He briefly worked for the Atomic Energy Authority, but lost his security clearance following a jaunt to Moscow for a communist youth festival and peace mission, when he was arrested by the KGB. He resigned and turned to Photography in 1960.

Hoppy embodied the world of 60s: a new emerging world of youth culture, alongside a world of social change and freedom. Through his insightful, raw and beautiful photos he documented this incredible time of change. In a relatively short period of time, Hoppy’s diverse images of British youth and subcultures of the 60s reached an iconic status.

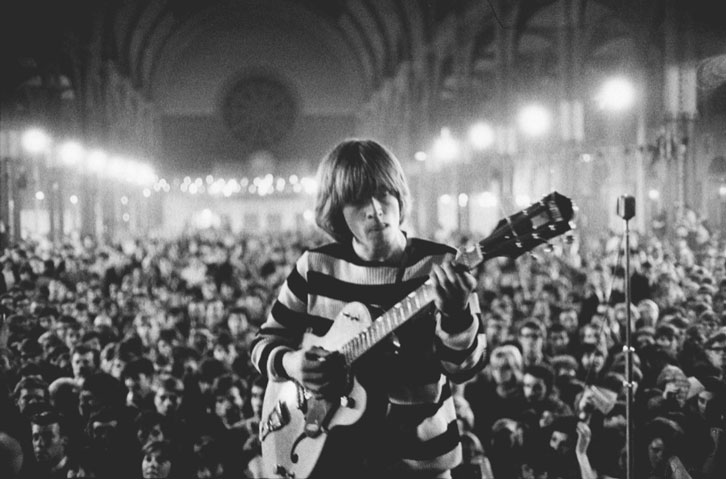

When the 60s began, he was young, inquisitive, energized and in London. He was working as a news photographer for the Sunday Times as well as for Melody Maker and Peace News. This meant that he was taking pictures of everything from visiting Jazz and Blues Artists, through CND’s Easter marches from Aldermaston, to The Rolling Stones and The Beatles on their first wave of stardom, with a few fashion models in between who wanted to build up their portfolios.

Hoppy recorded the mood of the fast-changing decade and documented many genres – peace marches, poetry readings with a naked Allen Ginsberg and photographed twentieth century heroes such as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. In stark contrast and most poignantly Hoppy also shot the seedier side of London: grubby tattoo parlours, child poverty, bikers cafes, prostitutes, fetishists and sex workers in their small bed-sits. These images have a lasting humility which is rarely seen.

In 1965 he sets up Notting Hill Free School – a major factor in bringing together organisational players in Notting Hill Carnival. He co-founded Britain’s first underground newspaper, the ‘International Times’ (the forerunner of Time Out Magazine), co-established a publishing company, promoted Pink Floyd and set up London’s first all-night psychedelic club, the UFO, where Jimi Hendrix would play. Around this time Hoppy gathers together names, addresses and telephone numbers of 100 ‘movers and shakers’ in London and circulates them to each other. This is later seen as beginning what would become UK counterculture.

By June 1967, Britain’s fertile and diverse counterculture took much of its inspiration from Hoppy – he was the closest thing the movement ever had to a leader and became known as the ‘King of the Underground’. Revolutions are, almost by definition, factional, but during those golden years, the working-class anarchists, vaguely aristocratic bohemians, musicians, crusaders, poets and dropouts were united in their respect and affection for Hoppy.

His status as a leader of this amorphous movement had led to his downfall – Hoppy’s flat was raided, a small amount of hash was found, leading to his arrest and a prison sentence of nine months.

At his trial, he attacked the prohibition of drugs and, having been branded a “pest to society” by the judge, was handed a ludicrously vindictive jail term in Wormwood Scrubs Prison. Outrage at the sentence inspired a “Free Hoppy March” to Trafalgar Square, ubiquitous graffiti and a full-page protest in the Times, paid for by Paul McCartney, calling for legalisation of marijuana, signed by many illustrious names – including all four Beatles. Despite being a major cause célèbre, it didn’t get a day knocked off Hoppy’s sentence.

“I served six months in the Scrubs. Mick and Keith were also there after their drug bust. I said hello, but they were only there for two or three days. They had friends in all the right places!”

— Hoppy

At the end of the 60s, Hoppy turned to video as an art form and educational tool, researching the social uses of video for UNESCO, the Arts Council etc. Later on, he worked as a technical journalist, co-authored distance-learning video training courses, explored macro photography of plants, co-authored academic papers and just never stopped being cool.